NSTEMI (Non ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction) & Unstable Angina: Diagnosis, Criteria, ECG, Management

Non ST Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes (NSTE-ACS): Non ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction (NSTEMI) and Unstable Angina (UA)

The focus of this chapter is the diagnosis and management of patients with Non ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction (NSTEMI) and unstable angina (UA), which are collectively referred to as NSTE-ACS (Non ST Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes). This chapter deals with the pathophysiology, definition, criteria and management of patients with NSTEMI and unstable angina. Although ECG changes in NSTEMI and unstable angina have been discussed previously (refer to Classification of Acute Coronary Syndromes, and Ischemia and the ST Segment and ST segment depressions), a rehearsal of ECG characteristics and criteria is provided here. Management (treatment) of NSTEMI and unstable angina will be discussed in detail. The clinical definitions and recommendations presented in this chapter are in line with recent guidelines (2020) issued by the American Heart Association (AHA), American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the European Society for Cardiology (ESC). The chapter will start with basic concepts of NSTEMI and unstable angina and then elaborate the discussion gradually.

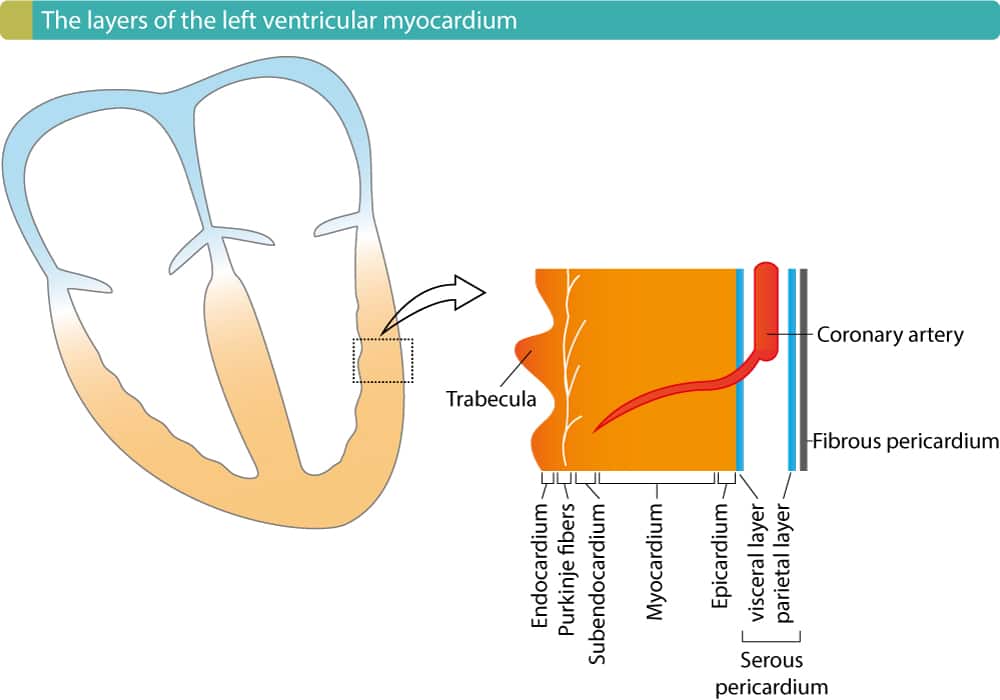

As in STEMI, the hallmark of NSTEMI and unstable angina is chest pain (chest discomfort). However, the chest pain caused by NSTEMI and unstable angina is less severe than the pain in acute STEMI. This is explained by the fact that NSTEMI and unstable angina are caused by partial (incomplete) coronary artery occlusions; a partial occlusion results in a reduction of coronary blood flow and this causes subendocardial ischemia (i.e ischemia that only affects the subendocardium). STEMI, on the other hand, is caused by a complete coronary artery occlusion, which results in complete stop of blood flow and thus more extensive myocardial ischemia (referred to as transmural ischemia). Yet, the pain caused by NSTEMI and unstable angina is considerable and most patients are therefore markedly affected. Other symptoms – such as dyspnea, cold sweat, nausea etc – are also common in NSTEMI and unstable angina (please refer to Approach to Patients with Chest Pain).

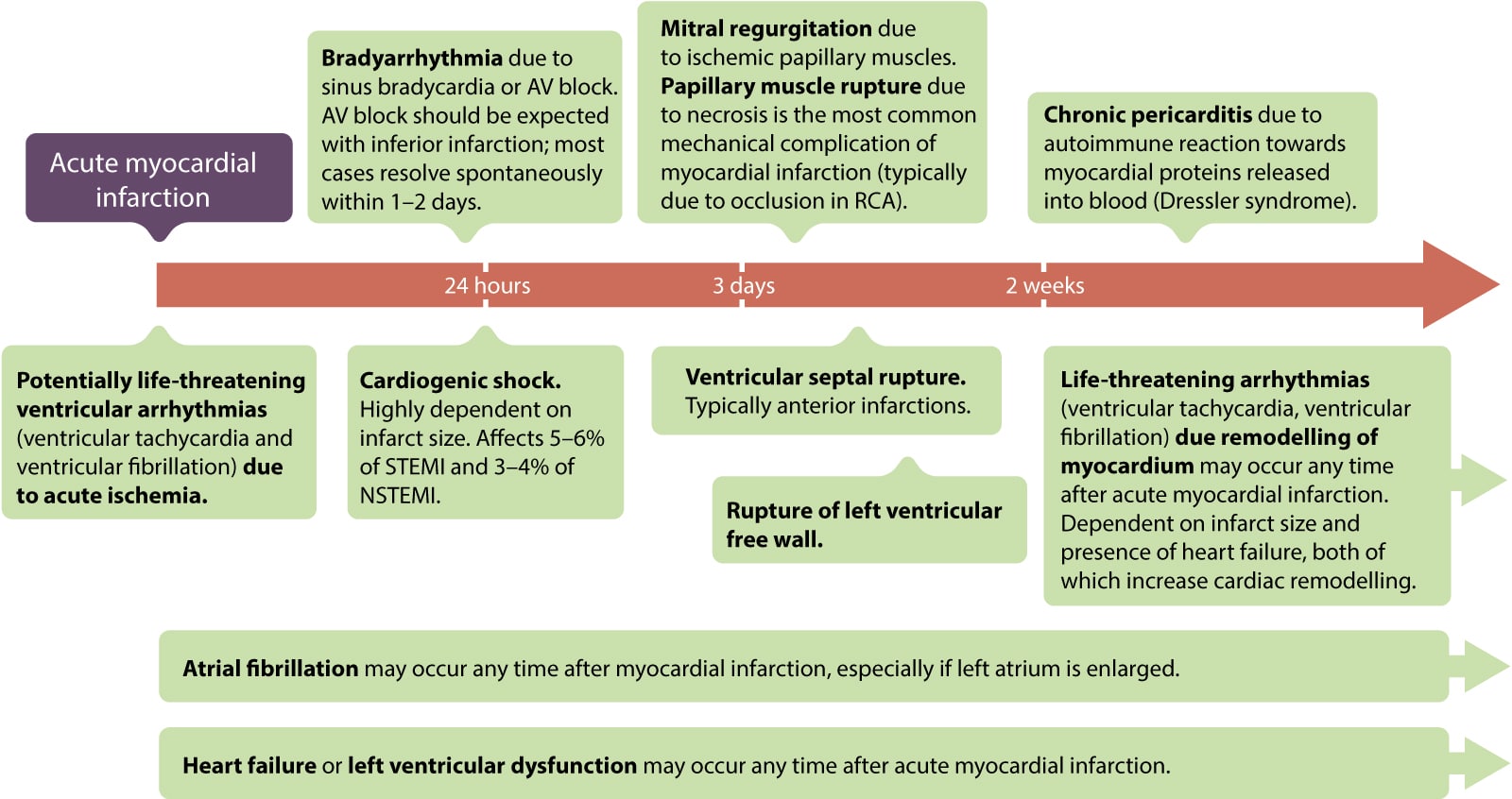

As in patients with STEMI, those with NSTEMI and unstable angina are at considerable risk of developing life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias (ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation) and subsequently cardiac arrest. Although ventricular arrhythmias may occur any time after coronary artery occlusion, the vast majority occur within the first hour(s). Hence, the majority of all fatal cases of NSTEMI and unstable angina occur during the first hour(s). This underlines the importance of prompt diagnosis and intervention.

NSTEMI & unstable angina: different but similar

NSTEMI and unstable angina are different in one fundamental aspect: NSTEMI is by definition an acute myocardial infarction, whereas unstable angina is not an infarction. Unstable angina is only diagnosed if there are no evidence of myocardial infarction (necrosis). However, unstable angina is considered an acute coronary syndrome because it is an imminent precursor to myocardial infarction. Approximately 50% of patients with unstable angina progress to myocardial infarction within 30 days if left untreated. Moreover, the pathophysiology of NSTEMI and unstable angina is very similar: both are due to partial (incomplete) coronary artery occlusions, which implies that there remains residual blood flow in the artery. Moreover, management of NSTEMI and unstable angina is virtually equal and this explains why NSTEMI and unstable angina have traditionally been grouped together.

The chain of care in NSTEMI and unstable angina

Management of patients with acute coronary syndromes is permeated by the mantra time is myocardium, which refers to the progressive loss of myocytes following occlusion of a coronary artery. The size, location and duration of the occlusion is of prime importance but additional factors may also influence the infarction process, which is normally completed between 2 and 12 hours after symptom onset. The continuous loss of myocardium and the electrical instability calls for prompt diagnosis and treatment. Therefore, most communities have developed a regional system of care which includes the dispatch center, ambulance, emergency department, catheterization laboratory and cardiology ward. These units must act in concert to reduce the delay from symptom onset to treatment.

General principles of management of NSTEMI and unstable angina

Management of NSTEMI and unstable angina has improved dramatically over the past three decades and continues to evolve. NSTEMI and unstable angina are treated with anti-ischemic (to alleviate ischemia) and anti-thrombotic (to counteract the thrombus) agents. Most patients undergo coronary angiography within 48 hours or earlier if the patient is at high risk of death or other complications. Symptoms, hemodynamic status, ECG changes, troponin levels and comorbidities dictates whether angiography should be performed promptly. Interestingly, acute angiography (which is routine in STEMI) has never proven to reduce mortality or morbidity in NSTEMI or unstable angina. Guidelines do not recommend acute angiography in patients with NSTEMI or unstable angina. Guidelines recommend that PCI should be done within 24 hours of NSTEMI/unstable angina, if possible. Low-risk patients may be evaluated after 48–72 hours. Management is discussed in detail below.

Note that STEMI (ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction) is discussed in a separate chapter.

Definitions and classification of acute coronary syndromes (acute myocardial infarction)

The term acute coronary syndrome (ACS) has been discussed previously (refer to Introduction to Ischemic Heart Disease and Classification of Acute Coronary Syndromes). An acute coronary syndrome is caused by an abrupt reduction in coronary blood flow. The reduction in coronary blood flow is due to atherothrombosis, which occurs when an atherosclerotic lesion disrupts. Atherotrombosis obstructs coronary blood flow and causes ischemia in the myocardium supplied by the artery. Figure 1 shows the process from atherothrombosis to classification of acute coronary syndromes.

As discussed previously, ischemia results in ECG changes. In fact, the type of ischemia will determine which type of ECG changes that occur. Hence, acute coronary syndromes can be classified according to the ECG. The classification is based solely on the presence of ST segment elevations. This simple classification separates two rather different syndromes, namely STE-ACS (which includes STEMI) and NSTE-ACS (which includes NSTEMI and unstable angina). Details follow:

- STE-ACS (ST Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome) is defined as an acute coronary syndrome with ST elevations on ECG. STE-ACS has been discussed previously (refer to STEMI – ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction and ST Elevations in Ischemia and Infarction). Virtually all patients with STE-ACS develop myocardial infarction, which is then classified as STEMI (ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction).

- NSTE-ACS (Non ST Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome): All acute coronary syndromes that do not meet criteria for STE-ACS are automatically classified as NSTE-ACS. For the sake of clarity: NSTE-ACS is defined as an acute coronary syndrome without ST elevations on ECG. The majority of patients with NSTE-ACS will exhibit elevated troponins, which is evidence for myocardial infarction and therefore defines the condition as NSTEMI (Non ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction). Cases who do not display elevated troponins are classified as unstable angina (UA). The vast majority of patients with NSTEMI or unstable angina present with ST segment depressions and/or T-wave inversions on ECG.

NSTE-ACS is accordingly subdivided into NSTEMI and unstable angina, depending on whether troponin levels are increased. Elevated troponins (with a pattern consistent with myocardial necrosis; refer to Diagnosis of Acute Myocardial Infarction) is evidence for myocardial infarction (i.e NSTEMI), whereas normal troponins rule out myocardial infarction (i.e unstable angina). Figure 2 presents the natural history and classification of acute coronary syndromes.

![Figure 2. Classification of acute coronary syndromes into STE-ACS (STEMI, ST elevation myocardial infarction) and NSTE-ACS (Non STEMI and unstable angina [UA]).](https://ecgwaves.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/acute-coronary-syndrome-nstemi-diagnosis-criteria-myocardial-infarction-unstable-angina-ecg.jpg)

Epidemiology of NSTEMI and unstable angina

Mortality in acute myocardial infarction has declined by 50% during the last three decades. This is explained by increased use of revascularization (percutaneous coronary intervention or fibrinolysis), advances in anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents, as well as aggressive primary preventive strategies using statins, blood pressure lowering drugs and antidiabetic drugs. Reduced smoking rates have certainly also contributed to the observed trends.

In 1990, STEMI accounted for roughly 50% of all acute myocardial infarctions. The incidence of STEMI has declined gradually since then. Currently, STEMI represents 25–40% of all cases of acute myocardial infarction. During the same period, NSTEMI increased from 50% to 60–75% of all infarctions. This is explained by the implementation of increasingly sensitive biomarker (troponin) assays for detection of myocardial necrosis (i.e infarction). In 2017 it was possible to detect myocardial infarctions 100 times smaller than what was possible in 2001. Hence, many patients who would have previously been diagnosed as unstable angina are nowadays classified as NSTEMI. It is expected that the proportion classified as unstable angina will continue to decline as troponin assays become more sensitive.

Despite the advances in management and detection of NSTEMI and unstable angina, these conditions cause considerable mortality and morbiditiy worldwide.

NSTEMI and unstable angina are caused by partial (incomplete) occlusions

The severity of acute coronary syndromes depends mainly on the location, size and duration of the occlusion. Considering the location, proximal occlusions are more severe than distal occlusions, simply because a proximal occlusion will affect more artery branches and therefore more myocardium. With respect to the size of the occlusion, it is obvious that a total (complete) occlusion will be more devastating than a partial (incomplete) occlusion. It actually turns out that STEMI is caused by total occlusions (located proximally); such occlusions result in transmural ischemia/infarction, which implies that the ischemia/infarction stretches from the endocardium to the epicardium in the affected region. NSTEMI and unstable angina, on the other hand, are due to partial (incomplete) occlusions, which means that some blood flow remains in the artery; such occlusions result in subendocardial ischemia/infarction, which implies that only the subendocardial layer is affected. The reason why the subendocardium is affected by partial occlusions has been discussed previously (refer to Classification of Acute Coronary Syndromes and Myocardial Infarction). Refer to Figures 1, 2 and 3.

Acute and long-term complications of NSTEMI and unstable angina

The acute complications of NSTEMI and unstable angina are similar to those seen in STEMI, but occur at lower rates. Please refer to Acute and Long-Term Complications of STEMI for details. Figure 4 summarizes the complications.

ECG in NSTEMI & unstable angina

NSTEMI and unstable angina typically cause ST segment depressions, which are frequently accompanied by negative (inverted) T-waves or flat T-waves. Importantly, leads which display ST depressions do not necessarily reflect the ischemic area. This implies that ST depressions in leads V3–V4 are not necessarily due to anterior wall ischemia. Similarly, ST depressions in leads II, aVF and III does not imply that the ischemia is located to the inferior wall. In other words, ST depressions do not localize the ischemic area and therefore the ECG cannot be used to determine the location of ischemia in patients with NSTEMI or unstable angina. This contrasts against ST elevations, which are indicative of the ischemia area (refer to Localization of Acute Myocardial Ischemia and Infarction for details).

Ischemic ST depressions are characterized by a horizontal or downsloping ST segment. North American and European guidelines assert that the ST segment must be either downsloping or horizontal, otherwise ischemia is unlikely to be the cause (Figure 5). An in-depth discussion on ST depressions are provided in the chapter ST Segment Depressions in Ischemia and Infarction.

ECG criteria for the diagnosis of NSTEMI and unstable angina

Criteria for ischemic ST segment depression

- New horizontal or downsloping ST segment depressions ≥0,5 mm in at least two anatomically contiguous leads.

Criteria for ischemic T-wave inversions

- T wave inversion ≥1 mm in at least two anatomically contiguous leads. These leads must have evident R-waves or R-waves larger than S-waves.

Pathological (infarction) Q-waves

Pathological Q-waves arise if the infarction is extensive, which is usually not the case in patients with NSTEMI. Hence, patients with NSTEMI typically do not develop pathological Q-waves. However, in some instances, the subendocardial injury may be extensive in patients with NSTEMI, which may result in pathological Q-waves. Note that unstable angina does not result in any QRS changes because the condition does not lead to myocardial necrosis (infarction).

Normal ECG in patients with NSTEMI or unstable angina

A minority of patients with NSTE-ACS display normal ECG on arrival. It is unusual, however, to display a normal ECG throughout the course. Most patients with normal ECG on arrival will develop some ECG changes during the process. Moreover, a normal ECG on arrival does not rule out myocardial ischemia/infarction; some infarctions are too small to engender ECG changes and others may be dynamic over time and initially present without ECG changes.

Clinical assessment and initial evaluation of patients with NSTEMI and unstable angina

Early management in NSTEMI and unstable angina

Patients with NSTEMI or unstable angina must be referred immediately to the emergency department (ED). The patient should preferably be transported by the emergency medical services (EMS). Studies have demonstrated several benefits of utilizing the EMS, such as reduced delay to evidence-based therapies and reduced delay to be seen by ED physician. Yet, the EMS is heavily underutilized in patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI); according to the NRMI registry, approximately half of patients with AMI use the EMS. Moreover, studies also demonstrate that patients who use the EMS have higher mortality and morbidity, as compared with the overall population with acute coronary syndromes. This is explained by the fact that patients who use the EMS have more comorbidities, higher prevalence of cardiovascular disease and are generally older.

The EMS should immediately assess vital functions and address hemodynamic, electrical and respiratory instability. If the patient is hemodynamically stable, a brief history (focus on coronary risk factors and current symptoms) and risk stratification should be performed. Evidence-based therapies can be started already in the ambulance. Oxygen, morphine, nitrates and aspirin are safe and effective to administer en route to hospital. A defibrillator must always be ready and venous access should be established. Vital parameters include heart rate, heart rhythm, blood pressure, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation and consciousness. ECG and chest pain (or other symptoms suggestive of ACS) must also be evaluated.

Prehospital 12-lead ECG

A 12-lead ECG should be performed at earliest opportunity and evaluated immediately. Prehospital personnel have proven to be highly capable of recognizing ischemic ECG changes and they may transmit ECGs electronically to the hospital for further evaluation. If the initial ECG is not diagnostic, additional ECGs can be performed if time and other circumstances allow. Although prehospital troponin analysis is available, it is generally discouraged since it does not improve survival.

Emergency department (ED)

The same clinical parameters must be assessed in the emergency department (ED). Assessment of complications (e.g heart failure) is important as such may require additional interventions. New 12-lead ECGs are performed and serial recordings are acquired if appropriate. Guidelines state that a 12-lead ECG should be evaluated within 10 minutes after patient arrival in the ED. Supplementary leads (V3R, V4R, V7, V8 and V9) may be necessary. Continuous monitoring with 12-lead ECG (ST segment monitoring) increases the detection of ischemia, but such equipment is frequently unavailable.

Cardiac troponin I or T levels are obtained at presentation and 3 to 6 hours after symptom onset. Rising or falling values, with at least one value above the upper normal limit is evidence for acute myocardial infarction. Note that normal troponins do not rule out myocardial infarction until 6 hours after the latest episode of symptoms (it may require 6 hours for troponins to increase following myocardial necrosis).

Objective evidence of myocardial ischemia/infarction: ECG & cardiac troponins

Patients with objective evidence of myocardial ischemia – i.e ischemic ECG changes or elevated troponins – should receive anti-ischemic and anti-thrombotic agents immediately (provided that there are no contraindications). Patients without objective evidence of myocardial ischemia (i.e those who only present with symptoms, such as chest pain) should be observed in a chest pain unit so that serial ECGs and troponins can be evaluated. Guidelines recommend that patients without objective evidence of ischemia should undergo exercise stress testing once their condition has stabilized. Stress myocardial perfusion imaging, stress echocardiography or CTCA (computerized tomography of coronary arteries) are more expensive alternatives but offer greater sensitivity and specificity.

Management in the emergency department (ED)

Anti-ischemic and anti-thrombotic agents should be given without delay if the suspicion of NSTEMI or unstable angina is strong, provided that there are no contraindications. Among the potentially life-threatening differential diagnoses, aortic dissection is the most important one since it is a contraindication to several agents used in acute coronary syndromes.

All patients with NSTE-ACS (NSTEMI or unstable angina) are treated similarly with respect to anti-ischemic and anti-thrombotic drugs. Management must, however, be individualized with respect to coronary angiography (PCI). The majority of patients should undergo angiography within 24 hours, but high risk patients should be evaluated with angiography earlier. Guidelines recommend the use of validated risk models to estimate the risk of acute myocardial infarction, 30-days and 1-year mortality. TIMI, GRACE and PURSUIT are such risk models and they are all easy to use. The higher the estimated risk, the earlier should angiography be performed.

Calculate TIMI Risk Score for NSTEMI / Unstable Angina

| TIMI SCORE | 30-days mortality | 30-days acute MI | Probability of revascularization |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0-1 | 1,2% | 2,3% | 1,2% |

| 2 | 1,0% | 2,1% | 6,0% |

| 3 | 1,7% | 3,7% | 9,5% |

| 4 | 2,5% | 5,0% | 12,2% |

| 5 | 5,6% | 8,5% | 14,3% |

| 6-7 | 6,5% | 15,8% | 20,9% |

As always in patients with acute coronary syndromes, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) should be withheld during the acute phase. NSAIDs (except from aspirin) increase mortality in patients with acute coronary syndromes.

Evidence-based therapies for NSTEMI

Oxygen in acute NSTEMI or unstable angina

Oxygen is given if oxygen saturation is <90%. There is no evidence that oxygen confers any benefit.

There is no data to support or refute any benefit of oxygen in patients with NSTEMI or unstable angina. Guidelines recommend oxygen if oxygen saturation is <90%. Oxygen is also appropriate in patients with pulmonary edema, heart failure and mechanical complications (free wall rupture, ventricular septum defect, mitral prolapse) of NSTEMI or unstable angina.

Analgesics in acute NSTEMI & unstable angina

Morphine sulfate is administered to all patients with acute NSTEMI or unstable angina. Caution is required in patients with hypotension.

Pain activates the sympathetic nervous system which leads to (1) peripheral vasoconstriction, (2) positive inotropic effect and (3) positive chronotropic effect. This increases the workload on the heart and therefore aggravates the ischemia. Adequate doses of analgesics are necessary to prevent the potentially harmful effects of the sympathetic nervous system. Analgesics also alleviate pain and relieves anxiety.

Morphine is the drug of choice. Morphine also causes dilatation of the veins, which reduces cardiac preload. Reduction in preload results in reduced workload on the left ventricle and this may alleviate both ischemia and severity of pulmonary edema.

The required dose of morphine depends on age, body mass index (BMI) and hemodynamic status. Reduced doses are warranted in patients with hypotension because morphine may cause additional vasodilatation. An initial dose of 2 to 5 mg IV is recommended. Injections may be repeated every 5 minutes until 30 mg have been administered. Naloxone (0.1 mg IV, and repeated every 10 minutes if necessary) may be administered if there are signs of morphine overdose. Morphine may cause bradycardia which can be managed with atropine 0.5 mg IV (repeated as necessary). If a total of 30 mg morphine is insufficient to relieve the pain, one should suspect aortic dissection.

NSAID (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) and selective cyclooxygenase II (COX-2) inhibitors are contraindicated (these drugs increase mortality in acute coronary syndromes).

Note that nitrates and beta blockers also exert analgesic effects (explained below). It is crucial that the use of morphine does not limit the use of beta blockers, since they potentiate each others negative hemodynamic effect and only beta blockers reduce mortality.

Nitrates (nitroglycerin)

Nitrates are administered to the vast majority of patients with STEMI. Nitrates do not affect the prognosis but relieves symptoms.

Nitrates cause vasodilatation by relaxing smooth muscle in arteries and veins. The ensuing vasodilatation reduces venous return to the heart which decreases cardiac preload. This reduces the workload on the myocardium and thus the oxygen demand. Nitrates therefore relieves ischemic symptoms (chest pain) and pulmonary edema.

A dose of 0.4 mg (sublingual or tablet) is given and may be repeated 3 times with 5 minute intervals. Nitroglycerin infusion should be considered if the effect is inadequate (severe angina) or if there are signs of heart failure. Infusion may be initiated with 5 μg/min and titrated up every 5 minutes to 10–20 μg/min. The dose is titrated until symptoms are relieved or a maximal dose of 200–300 μg/min is reached.

Nitrates should not be administered in (1) patients with hypotension, (2) suspicion of right ventricular infarction, (3) sever aortic stenosis, (4) hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy or (5) pulmonary embolism. Administration should proceed with caution if blood pressure drops >30 mmHg from baseline. As with morphine, use of nitrates must not limit the use of beta blockers and ACE inhibitors (these drugs affect blood pressure and heart rate).

Beta blockers in NSTEMI and unstable angina

Oral beta blockers should be given to all patients in maximal tolerated dose and continued indefinitely. Therapy should be initiated within 24 hours. Intravenous beta blockers is potentially harmful in patients with NSTEMI or unstable angina.

Beta blockers are likely to reduce morbidity and mortality. However, the evidence for beta blockers in NSTEMI or unstable angina is less robust than for STEMI. Beneficial effects of beta blockers have been demonstrated in the acute and long-term setting. Early studies demonstrated that beta blockers may reduce the risk of progression from unstable angina to NSTEMI.

Beta blockers have negative inotropic and negative chronotropic effect, which reduces heart rate (duration of diastole becomes prolonged), cardiac output and blood pressure. The workload on the myocardium is reduced and oxygen demand is subsequently reduced. Prolongation of diastole will give extra time for the myocardium to be perfused (the myocardium is perfused only during diastole). A large body of evidence – particularly in patients with STEMI but also in NSTEMI and unstable angina – demonstrates that beta blockers increase survival, reduce morbidity and improve left ventricular function. Beta blockers presumably also protect against ventricular tachyarrhythmias (ventricular tachycardia).

Treatment with beta blockers should start early within 24 hours, provided that the patient is hemodynamically stable. Starting with oral metoprolol 25 mg four times daily is recommended. The dose is titrated up until maximal tolerated dose or 200 mg is reached. Sustained-release preparations are preferred once the maximal dose is reached. Metoprolol, carvedilol and bisoprolol are all evidence based beta blockers.

Contraindications and caution

Beta blockers should be avoided or postponed in the following scenarios:

- Patients with acute heart failure should not be given beta blockers during the acute phase of NSTEMI or unstable angina. Once the heart failure is stabilized, beta blockers are extremely beneficial in heart failure and should therefore be initiated.

- Patients at risk of cardiogenic shock should not be given beta blockers due to the negative inotropic and chronotropic effect.

- Patients with first-degree AV block should perform a second ECG after initiation of beta blockers, since the first-degree AV block may progress to higher degrees of AV block. Second-degree and third-degree AV block (without pacemaker) are contraindications.

- Patients with obstructive pulmonary disease should be given beta-1 selective agents (e.g bisoprolol).

Nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (CCB)

Patients with continuing or recurring ischemia and contraindication to beta blockers may benefit from oral CCBs (e.g verapamil, diltiazem).

Calcium channel blockers are considered if the patient is intolerant to beta blockers. Verapamil and diltiazem reduce angina symptoms and may (evidence is vague) be beneficial in patients with NSTEMI or unstable angina. CCBs may occasionally be considered in patients with continuing or recurring ischemia despite appropriate use of beta blockers, nitrates and morphine.

Calcium channel blockers should be avoided as initial therapy in patients with significant left ventricular dysfunction, increased risk of cardiogenic shock, first-degree AV block, second-degree AV block or third-degree AV block (without a cardiac pacemaker).

Antithrombotic therapy

Antiplatelet agents

A loading dose of aspirin (160 mg to 320 mg) should be given immediately to all patients. Aspirin is then continued indefinitely (maintenance dose 80 mg daily).

A loading dose of a P2Y12-receptor inhibitor should also be given immediately and then continued for 12 months. There are three alternatives:

- Clopidogrel, 600 mg loading dose – The least effective of the P2Y12-receptor inhibitors.

- Prasugrel, 60 mg loading dose.

- Ticagrelol 180 mg loading dose – The preferred agent to be combined with aspirin.

Aspirin

Aspirin has an astonishing effect in NSTEMI and unstable angina: it reduces 30-days mortality by 50%. Aspirin is also effective in preventing re-infarction beyond 30-days and must never be discontinued without careful consideration. The optimal dose of aspirin is unknown but studies show that maintenance doses between 80 mg and 1500 mg are equally effective; hence, 80 mg is preferred as it minimizes the risk of gastrointestinal bleedings. Similarly, loading doses greater than 320 mg do not confer any additional benefit, which is why a loading dose of 320 mg is recommended.

Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT)

Optimal antiplatelet effect requires addition of either ticagrelol, prasugrel or clopidogrel. Combining aspirin with any of these is referred to as DAPT (dual antiplatelet therapy). An individual assessment of bleeding risk is warranted and DAPT should be avoided if the risk is high. DAPT is continued for 12 months in all patients. The indication is stronger in patients who undergo PCI with placement of stent.

Clopidogrel

Addition of clopidogrel to aspirin will additionally reduce the risk of death, stroke and acute myocardial infarction by 20%, at the expense of 28% increased risk of bleeding. A loading dose of 600 mg followed by maintenance dose of 80 mg daily is recommended. Clopidogrel is withheld 5 days before planned CABG (coronary artery bypass grafting). Although clopidogrel causes fewer bleedings than prasugrel and ticagrelol, it is less effective and therefore a secondary choice.

Prasugrel

As compared with clopidogrel, prasugrel offers a greater reduction in the risk of cardiovascular death, acute myocardial infarction, stroke and stent restenosis. Prasugrel is indicated (loading dose 60 mg, maintenance dose 10 mg) if PCI is planned and the patient is not already on clopidogrel. Prasugrel should be avoided if the risk of bleeding is high, as well as in patients with previous TIA (transient ischemic attack) or stroke. The maintenance dose is reduced to 5 mg daily in patients older than 75 years as well as in patients weighing less than 60 kg. Prasugrel is withheld 7 days before planned CABG.

Ticagrelol

As compared with clopidogrel, ticagrelol is more potent and has more rapid onset of effect. A loading dose of 180 mg is followed by a maintenance dose of 90 mg twice daily. As compared with clopidogrel, ticagrelol reduces the risk of cardiovascular mortality by 21% and acute myocardial infarction by 16%. Ticagrelol causes 19% more bleedings. The reduction in mortality and myocardial infarction outweighs the risk of bleeding, which is why ticagrelol is now recommended to all patients with NSTEMI or unstable angina (combined with aspirin).

Intravenous antiplatelet agents: Glycoprotein (GP) IIb/IIa receptor antagonists

GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors are administered in the catheterization laboratory. These drugs are highly potent platelet inhibitors which should be considered in high risk patients.

These agents (abciximab, tirofiban, eptifibatid, elinogrel) blocks the GP IIb/IIIa receptor which is located on the membrane of platelets and binds platelets to fibrinogen and von Willebrand factor. This class of drugs is actually the most potent platelet inhibition available. Randomized controlled clinical trials demonstrated that GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors reduce the risk of death and acute myocardial infarction among patients undergoing PCI (patients received aspirin and clopidogrel before GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors were administered during PCI). It is, however, unknown how to optimally administer GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors when administering DAPT.

Anticoagulants in NSTEMI and unstable angina

Fondaparinux is the drug of choice and should be given to all patients in the acute setting. Enoxaparin, heparin or thrombin inhibitors are secondary alternatives.

Fondaparinux

Fondaparinux (2,5 mg daily, treatment duration 4 to 5 days) is the first choice among the anticoagulants. Fondaparinux is as effective as enoxaparin in terms of reducing acute myocardial infarction, death and re-ischemia, but only causes half as many bleedings. Fondaparinux is therefore preferred over enoxaparin. Fondaparinux should be combined with unfractionated heparin (50 E/kg) in patients undergoing PCI to reduce the risk of catheter associated thrombosis during PCI.

Heparin

Unfractionated heparin (UFH) and low-molecular weight heparin (LMWH; dalteparin, enoxaparin) have been studied extensively in patients with NSTEMI and unstable angina. Enoxaparin (1 mg/kg subcutaneously every 12 hours) and dalteparin appear superior to UFH. Treatment is continued until a clinically stable condition is reached, which usually implies 2 to 8 days treatment.

Direct thrombin inhibitors

These drugs (hirudin, bivalirudin, argotroban) confer 20% reduced risk of death and acute MI as compared with UFH, at the expense of twice as many bleedings. Due to the high risk of bleeding, these drugs are only recommended in patients intolerant to heparin (heparin induced thrombocytopenia). Bivalirudin has been studied extensively and may be considered in patients undergoing PCI.

Angiography and revascularization (PCI, CABG)

Because the coronary occlusion in NSTEMI and unstable angina is partial, there is some residual perfusion (blood flow) in the ischemic zone. Therefore, revascularization (PCI) is less urgent and can generally be delayed without worsening the prognosis. Indeed, no study to date has proven any beneficial effect of immediate PCI in patients without ST elevations. Nevertheless, virtually all patients should undergo angiography to evaluate the coronary arteries. The purpose of coronary angiography is to determine whether there are any acute occlusions that can be treated with either PCI or CABG.

Features guiding the timing of revascularization for unstable angina or NSTEMI

- As a general rule, virtually all patients should undergo angiography within 72 hours.

- Immediate angiography (angiography within 2 hours) is recommended in patients with the following presentation:

- Malignant ventricular arrhythmias (sustained ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, cardiac arrest).

- Hemodynamic instability

- Heart failure – Killip III–IV)

- Severe chest pain (refractory angina) despite adequate use of anti-ischemic and analgesic agents.

- Early angiography (angiography within 24 hours) is recommended in patients with the following presentation:

- High-risk score (TIMI ≥4, GRACE >140)

- High troponins.

- Persistent high-risk or dynamic electrocardiographic changes.

- ST elevation not meeting STEMI criteria.

- Angiography after 25–72 hours is recommended in the following situations:

- No features requiring an immediate or early invasive strategy.

- Intermediate-risk score (TIMI 2−3, GRACE 109−140).

- Recurrent angina or signs of ischaemia despite therapies.

- Ejection fraction <40%, diabetes, renal insufficiency (estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min/1.73 m.), prior coronary artery bypass grafting, or percutaneous coronary intervention within 6 months.

If PCI is performed, the patient should receive a stent.

Patients who are not candidates for angiography are managed with an ischemia-guided strategy. This is reasonable in low-risk patients (TIMI ≤1, GRACE <109), patients at hospitals without PCI facilities, and on the basis of the patient’s preferences. An ischemia-guided strategy may be converted to an invasive strategy if the patient’s condition deteriorates.

Fibrinolysis (thrombolysis) in NSTEMI and unstable angina

Fibrinolysis may be harmful in patients without ST elevations and should therefore not be administered.

References

2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Non-ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes

Next chapter

Next chapter

Overview of Atrioventricular blocks (AV block)

Related chapters

Related chapters

Acute STEMI (ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction)

Introduction to Coronary Artery Disease (CAD)

Classification of Acute Coronary Syndromes & Myocardial Infarction: STEMI, NSTEMI & Unstable Angina

Clinical application of the ECG in chest pain and myocardial infarction

Myocardial infarction: diagnostic criteria, definitions and use of ECG

Approach to Patients with Chest Pain

ST Elevations on ECG: STEMI and Differential Diagnoses

STEMI (equivalents) without ST segment elevations

T-wave changes (inversion, hyperacute, flat) in ischemia / infarction

ST depressions on ECG: NSTEMI / UA and Differential Diagnoses

Left bundle branch block (LBBB) in acute myocardial infarction / ischemia

Factors that Modify the Natural Course in Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI)

View all chapters in Myocardial Ischemia and Infarction

References

2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction

Third Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (ACC, AHA, ESC joint statement)

GW Reed et al, The Lancet (2017): Acute Myocardial Infarction

JL Anderson et al, The NEw England Journal of Medicine (2017): Acute Myocardial Infarction