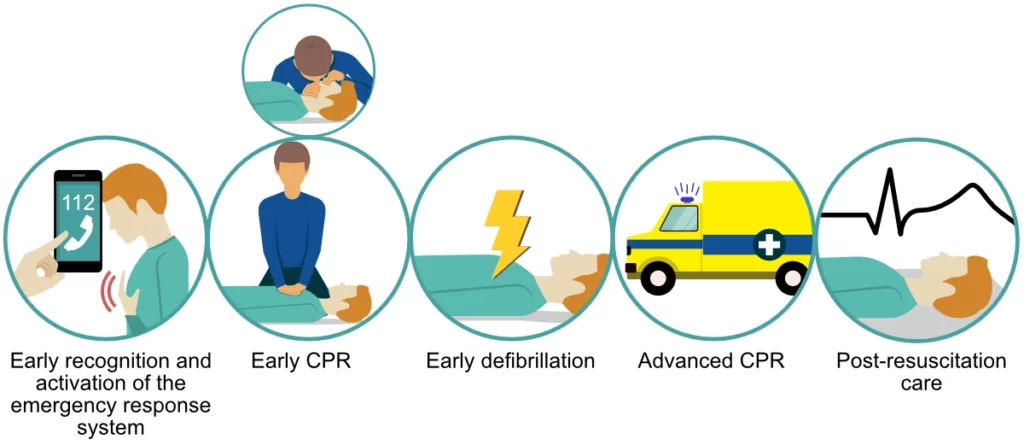

Time is the most critical factor for survival in cardiac arrest. Life-saving interventions must be initiated momentarily to maximize the probability of survival. Several actions must be executed systematically and rapidly. These actions constitute the chain of survival (Figure 1). The chain of survival in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) includes laymen (bystanders), the emergency dispatcher, first-responders (police, fire brigade, emergency services, security guards, etc.), paramedics, EMTs, nurses and physicians in the emergency medical system (EMS), as well as the hospital cardiac arrest team (CAT) and intensive care units and other units caring for resuscitated patients.

Although the required skills, complexity and costs of interventions increase with each step in the chain of survival, it is the first 3 actions that are fundamental for survival. Furthermore, the same actions (1 through 3) can be carried out by anyone, including laymen without prior training in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). Prompt delivery of chest compressions, ventilations and defibrillation (when possible) are the strongest determinants of survival in cardiac arrest. All subsequent actions require trained professionals (e.g endotracheal intubation, mechanical chest compressions, targeted temperature management, etc.) and are much less effective in terms of the number needed to treat (NNT).

The Number Needed to Treat (NNT) is the number of patients you need to treat to save one. If an intervention has an NNT of 10, then 10 people must be treated to save 1.

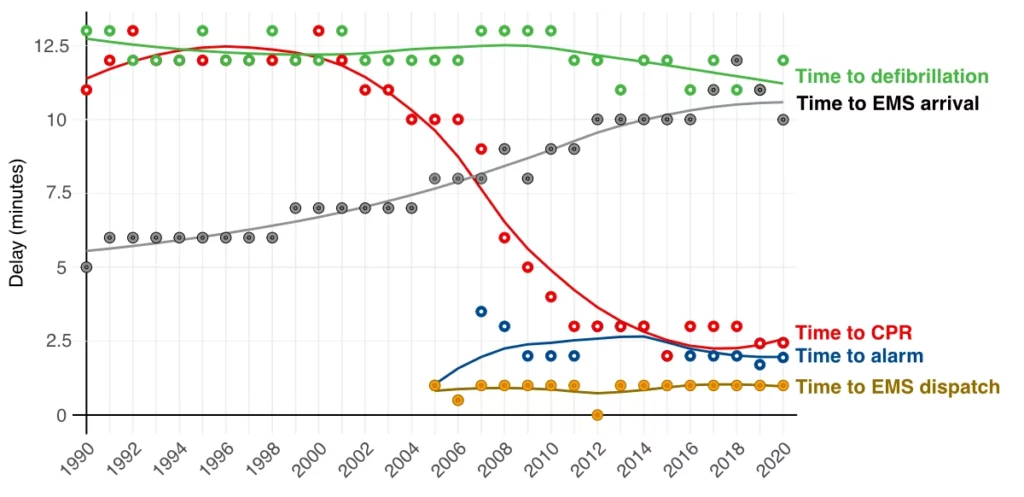

Thus, the greatest opportunities exist in the first few minutes, which is within the reach of bystanders, first-responders and the EMS. Unfortunately, several studies show that EMS response times have increased dramatically in recent years (Figure 2).

The chain of survival is only as strong as its weakest link, which means that all components of the chain must function and interact flawlessly to maximize survival.

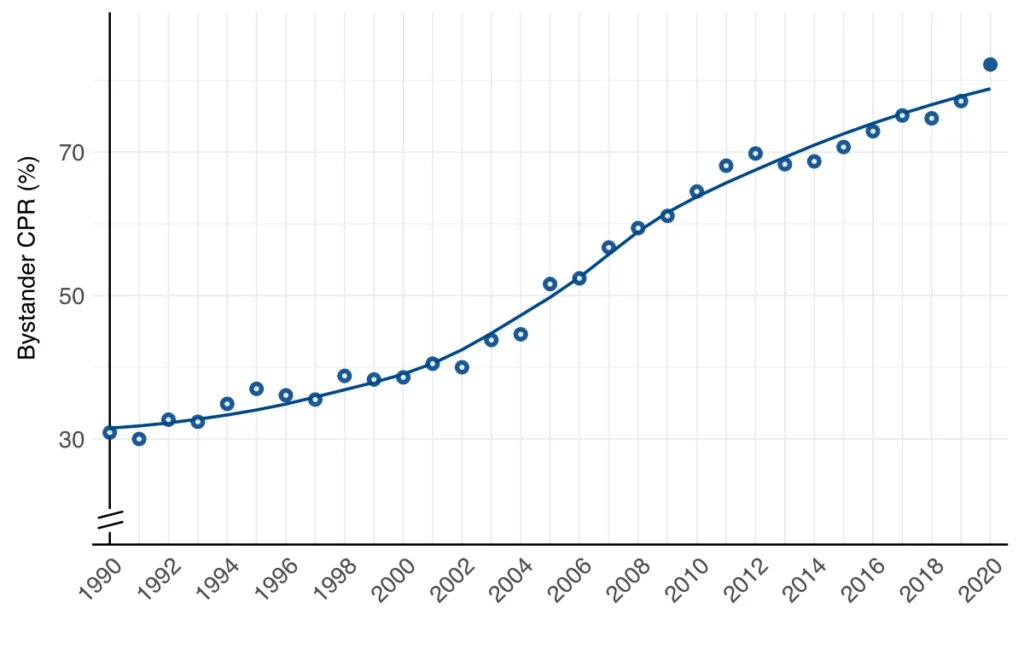

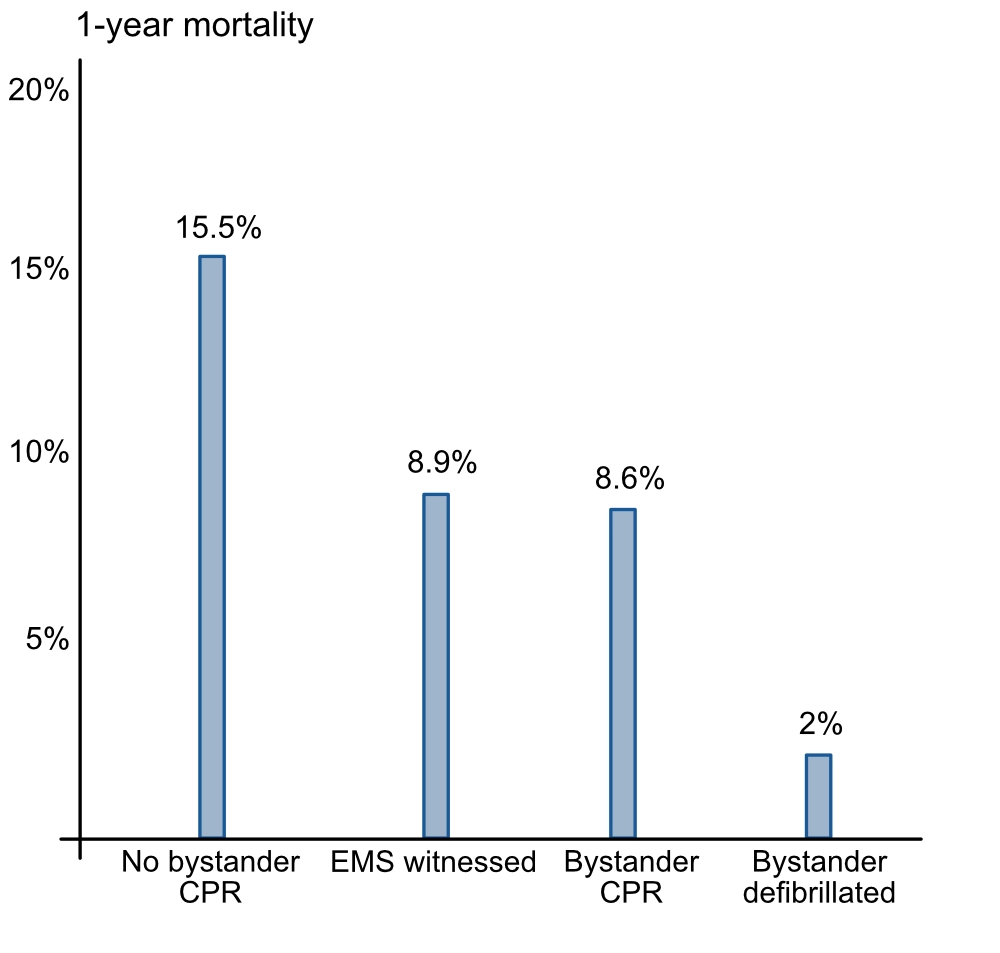

The single most pronounced improvement in the chain of survival is the dramatic increase in rates of bystander CPR (Figure 2). Bystander CPR was provided in approximately 30% of all cases of OHCA in 1990, as compared with 78% of all cases in 2020.

According to the chain of survival, the first task is to recognize cardiac arrest and alert the EMS (in OHCA) or cardiac arrest team (in IHCA). There are no risks in instructing a layperson to perform chest compressions on an unconscious individual. The potential benefit outweighs the risks. Several studies have demonstrated that bystander CPR performed by laymen doubles the probability of survival in OHCA (Hasselqvist-Ax et al).

To maximize the likelihood of bystander CPR, laymen in the community must be trained in basic cardiopulmonary resuscitation (BLS, basic life support). Training should be organized by certified instructors who design their courses in accordance with official guidelines (ERC, AHA, ACC).

The chain of survival

- EARLY RECOGNITION OF CARDIAC ARREST

- If no medical professional is nearby, bystanders must respond immediately by summoning help (calling the emergency dispatch center [911 in the US, 112 in Europe]) and initiate BLS (basic life support).

- BASIC CPR (BASIC LIFE SUPPORT, BLS)

- Chest compressions can be performed by anyone.

- If no bystander is trained in CPR, the emergency dispatcher will instruct the person via telephone (referred to as telephone CPR).

- Everyone in the emergency medical service (EMS) is trained in BLS.

- It is increasingly common to dispatch first-responders to OHCA, in addition to ambulances.

- Chest compressions are prioritized above ventilations.

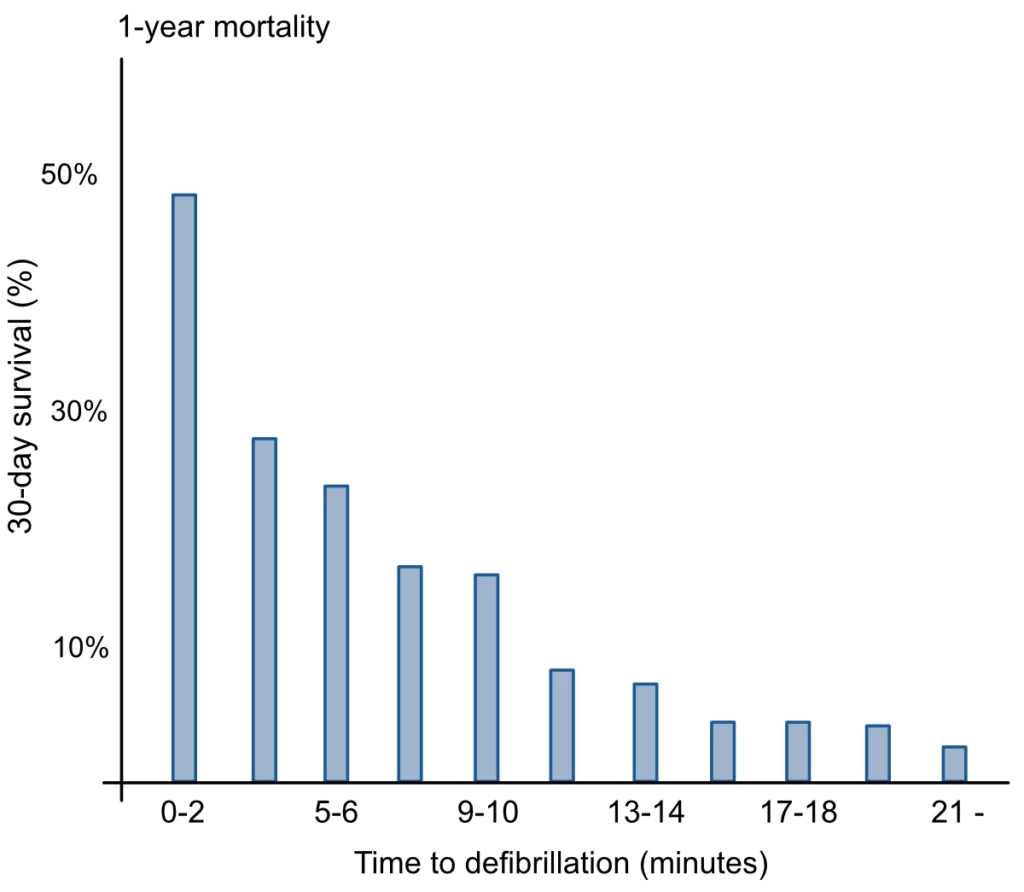

- DEFIBRILLATION

- Public defibrillators (AED, Automatic External Defibrillator) can be used by anyone.

- First-responders are often equipped with AEDs.

- ADVANCED CARDIOVASCULAR LIFE-SUPPORT (ACLS).

- POST-RESUSCITATION CARE

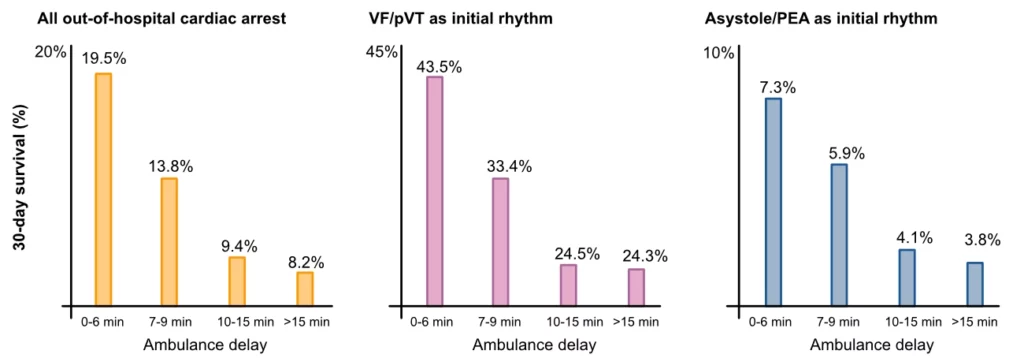

In densely populated areas, where ambulances are abundant and response times are short, survival is higher than in sparsely populated areas (Girotra et al). The impact of EMS response times is evident in Figure 4.

As mentioned above, survival increases 2-fold if a bystander immediately initiates CPR. Time to bystander CPR, defibrillation, and the arrival of the ambulance are undoubtedly the strongest predictors of survival (Kragholm et al)

Anyone responding to a cardiac arrest must introduce themselves, stating their name and profession, and clearly indicate the skills they can provide. Resuscitation equipment should be quickly located and retrieved. Effective communication is essential: speak clearly and loudly, use closed-loop communication to confirm tasks, and ensure that all actions proceed in parallel to maximize efficiency.

Roughly 20–25% of all out-of-hospital cardiac arrests have a shockable initial rhythm. The corresponding figure was 50% in 1990. This proportion is primarily influenced by the following two factors:

- Time to EMS arrival (and thus ECG recording), since shockable rhythms will degenerate into non-shockable rhythms (asystole, PEA). The gradual increase in EMS response times has resulted in a decrease in the proportion presenting with shockable rhythm upon EMS arrival.

- The proportion of cardiac arrests caused by ventricular arrhythmias, which is primarily a function of the prevalence of chronic and acute coronary artery disease, heart failure and other forms of structural heart disease. The incidence of fatal acute myocardial infarction has diminished dramatically in recent years, while the prevalence of heart failure has increased slightly.

Subsequent chapters will discuss how CPR can prolong the duration of shockable rhythms.

References

Girotra S, van Diepen S, Nallamothu B.K, et al. Regional variation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survival in the United States. Circulation. 2016; 133:2159 —2168

Matilda Jerkeman, Pedram Sultanian, Peter Lundgren, Niklas Nielsen, Edvin Helleryd, Christian Dworeck, Elmir Omerovic, Per Nordberg, Annika Rosengren, Jacob Hollenberg, Andreas Claesson, Solveig Aune, Anneli Strömsöe, Annica Ravn-Fischer, Hans Friberg, Johan Herlitz, Araz Rawshani. Trends in survival after cardiac arrest: a Swedish nationwide study over 30 years. European Heart Journal (2022). https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehac414

Kristian Kragholm, M.D., Ph.D., Mads Wissenberg, M.D., Ph.D., Rikke N. Mortensen, M.Sc., Steen M. Hansen, M.D., Carolina Malta Hansen, M.D., M.D., Ph.D., Kristinn Thorsteinsson, M.D., Ph.D. Leen Rajan, M.D., Freddy Lippert, M.D., Fredrik Folke, M.D., Ph.D., Gunnar Gislason, M.D., Ph.D., Lars Buker, M.D., D.Sc., Kirsten Fonager, M.D., Ph.D., Svend E. Jensen, M.D., Ph.D., Thomas A. Gerds, Ph.D., Christian Torp-Pedersen, M.D., D.Sc., and Bodil S. Rasmussen, M.D., Ph.D.. Bystander Efforts and 1-Year Outcomes in Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. N Engl J Med 2017; 376:1737-1747 DOI: 10.1056/Nejmoa1601891

Johan Holmén, MD, PhD, corresponding author 1, 2 Johan Herlitz, MD, PhD, 3 Sven‐Erik Ricksten, MD, PhD, 4 Anneli Strömsöe, RN, PhD, 5, 6, 7 Eva Hagberg, MD, 4 Christer Axelsson, RN, PhD, 3 and Araz Rawshani. Shortening Ambulance Response Time Increases Survival in Out‐of‐Hospital Cardiac Arrest. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020 Nov 3; 9 (21)

Malta Hansen C, Kragholm K, Pearson D.A, et al. Association of bystander and first-responder intervention with survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in North Carolina, 2010-2013. J Am Med Assoc. 2015; 314:255—264

Mikael Holmberg, Stig Holmberg, Johan Herlitz. The problem of out-of-hospital cardiac-arrest prevalence of sudden death in Europe today. Am J Cardiol. 1999 Mar 11; 83 (5B) :88D-90D.